Topic

AI

Published

January 2026

Reading time

13 minutes

AI Infrastructure: Compute (2/4)

Can new entrants break Hyperscale lock in?

AI Infrastructure: Compute (2/4)

Download ArticleResearch

AI Computing revolution, meet Cloud Oligopoly

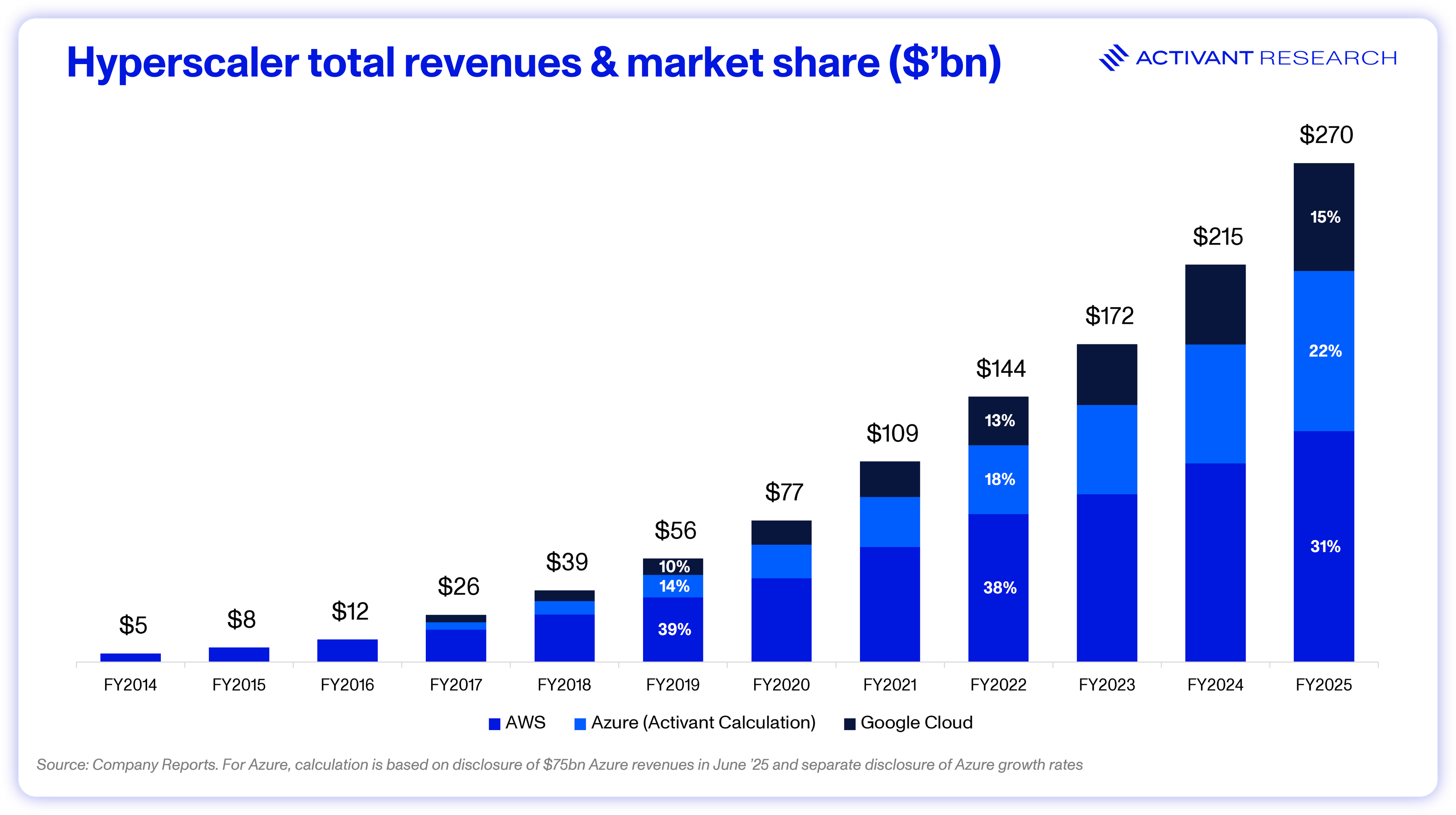

In our last article, we explored the legitimacy of the AI infrastructure build out - a 16x scale up of datacenter capacity set to support the next 5 years+ of AI compute growth into a ~$450bn+ market. However, a critical question remains: will the rapid growth of capacity, supply constraints, and specialized AI needs create space for new entrants to the compute market, or will the Hyperscalers hold their already so dominant ~70% share of the market?

~70%

Hyperscalar share of the compute market

We believe that the answer lies in a deep understanding of the competitive advantages that have allowed the Hyperscale cloud providers to build their incumbent position together with the history and path dependence that got them there. Know thy enemy.

No historical analysis of the cloud is complete with the statement that the advent of the cloud completely rewired the technology industry. Cloud providers offer the core compute, storage, and networking (IaaS) as well as key operating systems and middleware (PaaS) to enable any start-up or Fortune 500 enterprise to build and deploy applications without thinking about building and maintaining physical infrastructure. The cloud made it possible to start a company from your bedroom, completely shifted the economics of venture capital (funding go-to-market for companies with proven traction is a significant upgrade on buying servers for an idea) and spawned SaaS, a market, now worth ~$300bn with listed companies exceeding two-trillion dollars in market cap.1,2

Today, cloud computing is a digital utility as fundamental to the modern economy as the public electricity grid was to the industrial age. 55% of all workloads are on public cloud and IaaS & PaaS providers together turnover $420bn.3,4 Just as electrical utilities tend to concentration, most of the market is controlled by just three vendors, Amazon, Microsoft and Google (The Hyperscalers). Amazon’s early understanding of the importance of scale, obtained by building a massive logistics business to support their ecommerce operations, almost let them run away with the market. However, Microsoft leveraged their stickiness in enterprise IT to build a strong second place, and Google is fighting to be more than a bit-part 3rd player with AI integration.

The Amazon Playbook

The market for cloud computing as it exists today was largely invented and defined by Amazon. Its position is the direct result of a decade-long head start, a unique strategic philosophy born from its operational DNA, and a go-to-market motion that created a self-reinforcing cycle of adoption and expansion.

The Service-Oriented Mandate

A persistent but incorrect narrative suggests AWS was created to sell off excess server capacity from Amazon's retail business. It really started with an internal crisis. The company's e-commerce platform was built on a monolithic codebase that had become a severe blocker to scaling, as any changes required managing significant complexity and cross-functional collaboration. A now famous internal memo written by Jeff Bezos reoriented the firm around the “services” architecture that would eventually become Amazon Web Services.

All internal teams were required to expose their data and functionality through hardened, well-documented Application Programming Interfaces (APIs). Communication between teams was forbidden except through these service interfaces. A marketing team could now run a promotion that required a new web page and additional server infrastructure without having to walk to the IT room, or chat to the IT guys. Amazon built a platform for scaling generalizable IT infrastructure and productizing it for external use was just a natural next step.

Since there were so few firms in the early 2000s who confronted the web at the scale that Amazon did, or could grow at the rates that Amazon did, their insight into the services architecture was so unique that it gave them a near decade head start on the cloud. AWS was officially launched in 2006 with just one service, S3.5

The Primitives Masterstroke

The launch strategy, a simple and unopinionated storage service, reveals the foundational genius of Amazon’s strategy. Simple Storage Service (S3) for object storage and Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2) for virtual servers, were quintessential examples of Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS). They provided raw infrastructure components that developers could assemble in nearly any configuration imaginable – “primitives”.

This approach was a crucial contrast to the early offerings from competitors like Google's App Engine, which were more prescriptive Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS) environments. PaaS offerings required developers to build applications using a specific framework, creating immediate concerns about vendor lock-in. The IaaS model, however, imposed no such constraints. It allowed customers to perform a "lift-and-shift" migration, moving existing on-premises applications to the cloud with minimal re-architecting, dramatically lowering the barrier to adoption for established enterprises.

Simultaneously, it gave startups a blank canvas. By offering a pay-as-you-go model with no upfront costs, AWS eliminated what was historically the single largest capital expenditure for a new technology company: the purchase of server infrastructure. An entire generation of transformative companies, including Netflix and Airbnb, were built on AWS. As these startups succeeded, their AWS consumption scaled with them, creating a powerful and scalable customer acquisition pipeline. AWS won not just by being first, but by correctly identifying the right initial market wedge. The lesson is the same one that we outlined in our research on Open-Source AI - winning infrastructure players are those that provide maximum flexibility.

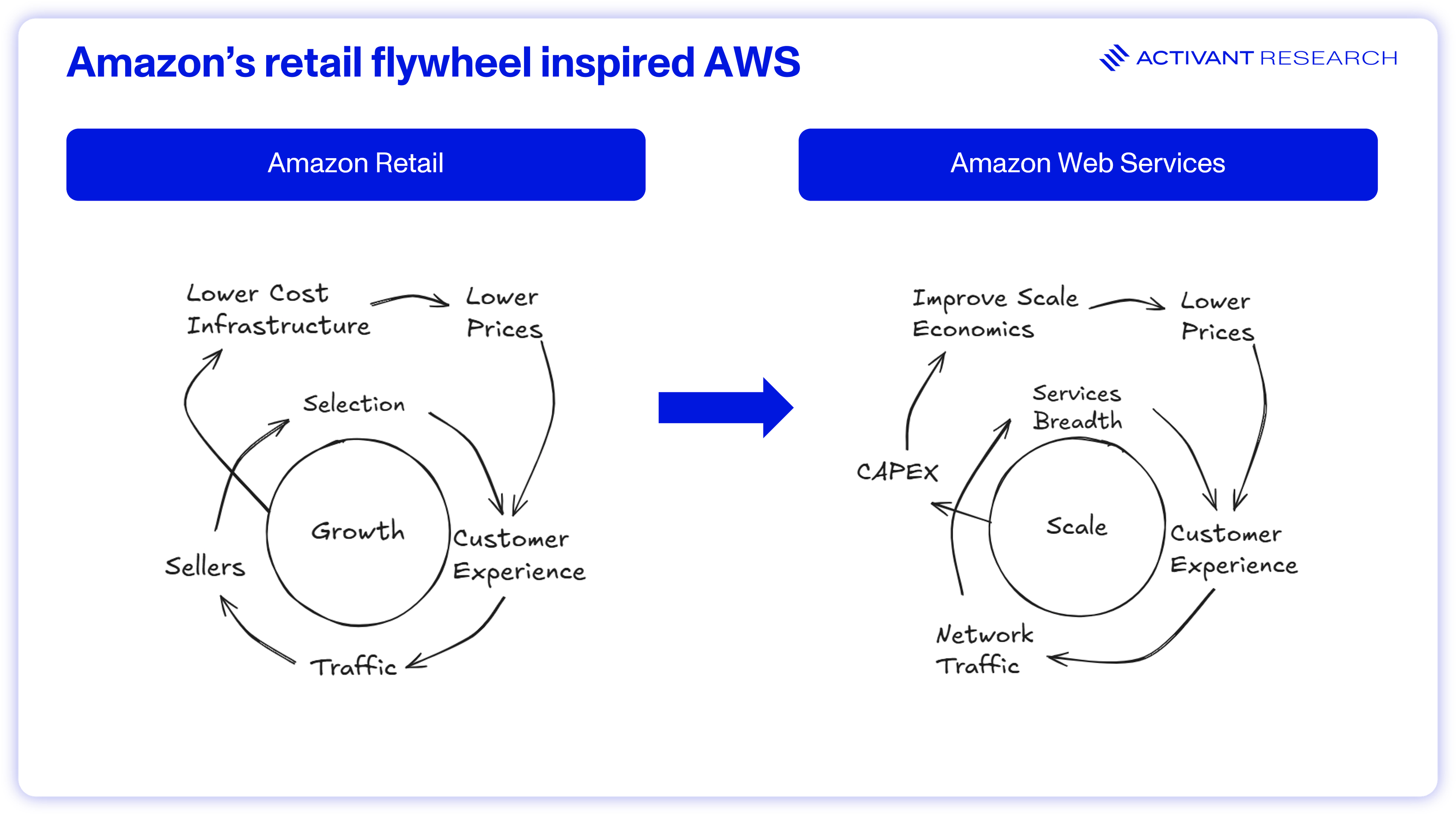

The Flywheel in Motion

The economic engine driving AWS's growth is a direct application of the "flywheel" concept that powered Amazon's retail business. This self-reinforcing loop begins with massive economies of scale, achieved through billions of dollars in global data center investment. This scale allows AWS to procure hardware and energy at significantly lower unit costs.

In a move that was counterintuitive to the high-margin world of enterprise IT, AWS systematically passed these cost savings on to customers through aggressive price reductions. By the spring of 2014, the company had already cut its prices 42 times, often in the absence of direct competitive pressure.6 Lower prices drove broader customer adoption, which in turn funded a relentless expansion of its service portfolio. This unparalleled breadth created its own powerful effect; as developers wove together multiple AWS-specific services, the complexity and cost of migrating to a competitor became prohibitively high.

Nadella’s Pivot and the Azure Comeback

While AWS was creating the cloud market, Microsoft, once the 800 pound gorilla of enterprise software, struggled. Through a profound strategic pivot and the masterful leveraging of its existing enterprise dominance, Microsoft transformed Azure from a struggling competitor into the clear number two Hyperscaler.

The Nadella Pivot

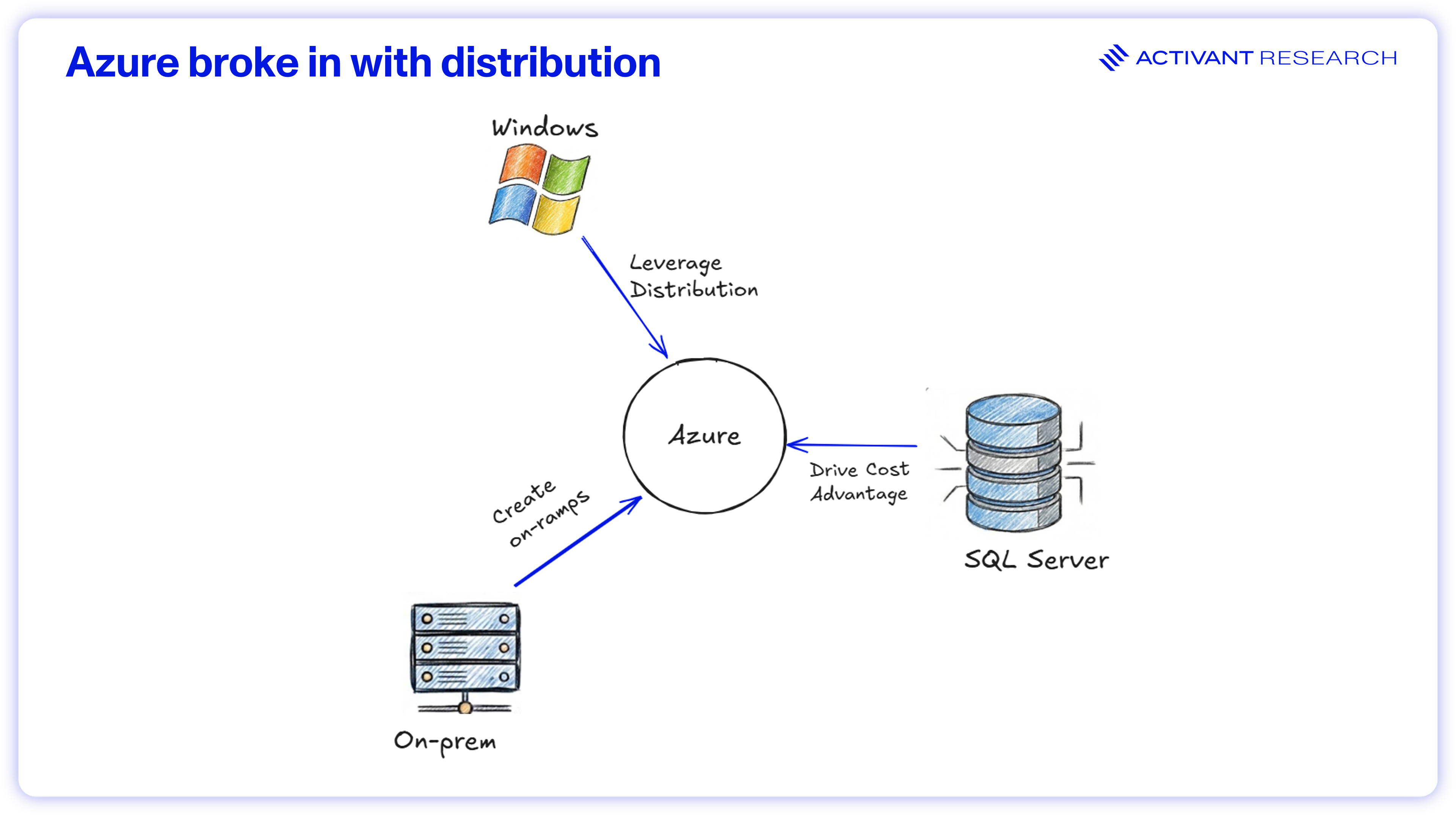

In its early years, Microsoft was handicapped by its deep allegiance to its Windows-centric, software licensing-based business model. The company's initial cloud offering, Windows Azure was a PaaS designed to extend the Windows ecosystem, an approach that failed to gain traction against the flexibility of AWS's IaaS primitives.

The critical turning point came with the appointment of Satya Nadella as CEO in 2014. Nadella, who had previously led the division that built Azure, initiated a fundamental cultural and strategic shift. He decisively de-prioritized the primacy of Windows and reoriented the entire company around a "cloud-first" strategy. This involved embracing open-source technologies like Linux on Azure, a move once considered heretical at Microsoft, and pivoting Azure's strategy to meet enterprise customers where they were, and that was both on premises and in the cloud.

Weaponizing Incumbency

Microsoft's most effective strategic maneuver was its early and unwavering commitment to hybrid cloud. While AWS initially promoted a purist, all-or-nothing approach to cloud migration, Microsoft recognized that large enterprises had decades of investment in their on-premises data centers. A wholesale migration was often technically and culturally infeasible.

Products like Azure Stack and Azure Arc were designed to extend the Azure control plane, its management and security services, directly into a customer's on-premise environment. This created a seamless bridge, allowing enterprises to migrate workloads at their own pace. This approach turned a company's legacy IT from an obstacle to cloud adoption into a direct on-ramp to Azure, positioning it as the pragmatic, safe choice.

Microsoft's most formidable weapon, however, is its unparalleled sales and distribution infrastructure. The company masterfully leveraged this engine to accelerate Azure's growth. A primary vehicle was the Microsoft Enterprise Agreement (EA), the multi-year software licensing contracts that are standard across the Fortune 500. Microsoft made it simple for CIOs to add Azure consumption to their existing EAs, often with significant discounts. This transformed the procurement of cloud services from a complex decision involving a new vendor into a simple line-item addition on a familiar contract.

Furthermore, Microsoft weaponized its existing software businesses. The Azure Hybrid Benefit program, for instance, allowed customers to apply their existing on-premises Windows Server and SQL Server licenses to Azure virtual machines, providing a substantial cost advantage over AWS. This practice, now a focus of antitrust investigations, effectively allowed Microsoft to convert its past market power into future cloud market share. Azure's success demonstrates that in enterprise technology, distribution can be a more powerful advantage than initial product leadership. It won by being the path of least resistance for the world's largest IT buyers.

Google gets enterprisey, with its own rules

As the third major entrant, Google Cloud Platform (GCP) pursued a differentiated strategy rooted in its own corporate DNA: a belief in technical superiority and a strategic embrace of open-source technology to reshape the competitive landscape.

The Kubernetes Gambit

Much like Microsoft, Google's initial foray into cloud computing with Google App Engine (GAE) was a strategic misstep. GAE was a classic PaaS offering that misread the market's demand for flexible, utility-style infrastructure.

Facing a distant third-place position, Google executed a brilliant pivot by open-sourcing its internal container orchestration system, known as Borg, and releasing it to the world as Kubernetes in 2014. This was a deliberate attempt to change the rules of the game. The core objective was to create a universal, open-source orchestration layer for deploying applications that could run on any infrastructure. The logic was to commoditize the underlying IaaS layer. If applications, packaged in portable containers, could be seamlessly moved between cloud providers, then the choice of the IaaS provider itself would become less critical. This would directly attack the primary advantage of AWS. By neutralizing the incumbent's head start, Google hoped to shift the competitive battleground upward to higher-value services like data analytics and machine learning, areas where it believed it held a significant technical advantage.

The Persistent Challenge

Despite its technological prowess, GCP has consistently faced a significant hurdle: a gap in its enterprise sales and support capabilities. Google's corporate DNA, forged in consumer search and automated advertising, was not naturally suited to the high-touch, relationship-driven cycles of large-scale enterprise IT. While AWS benefited from Amazon's culture of customer obsession and Microsoft leveraged its four-decade history of enterprise sales, Google had to build these capabilities from the ground up.

When asked which IT mega-vendor will be most critical to their organization's future, 54.8% of CIOs chose Microsoft and 6.0% chose AWS, while only 1.2% chose Google.7 Even with world-class technology, Google struggles to build the deep trust and strategic alignment that CIOs require from their core infrastructure partners. The Kubernetes gambit was strategically brilliant, but it failed to fundamentally alter the economic balance of power because it did not solve the customer's procurement and data gravity problems, keeping Google in third place. The lesson is clear: building the best tech can’t overcome distribution weaknesses.

54.8%

The proportion of surveyed CIOs who believe Microsoft will be most critical to their organization's future

A Taxonomy of Moats

The dominance of the major cloud providers is fortified by a series of powerful and self-reinforcing economic moats that create formidable barriers to entry for new competitors and significant barriers to exit for existing customers.

Minimum Effective Scale (MES)

The most fundamental cloud moat is the capital investment required to compete. Building and operating a global network of hyperscale data centers is one of the most capital-intensive undertakings in the modern economy. Economies of scale accrue to the leaders, and it becomes harder to compete with these scaled competitors as they improve their own operating model.

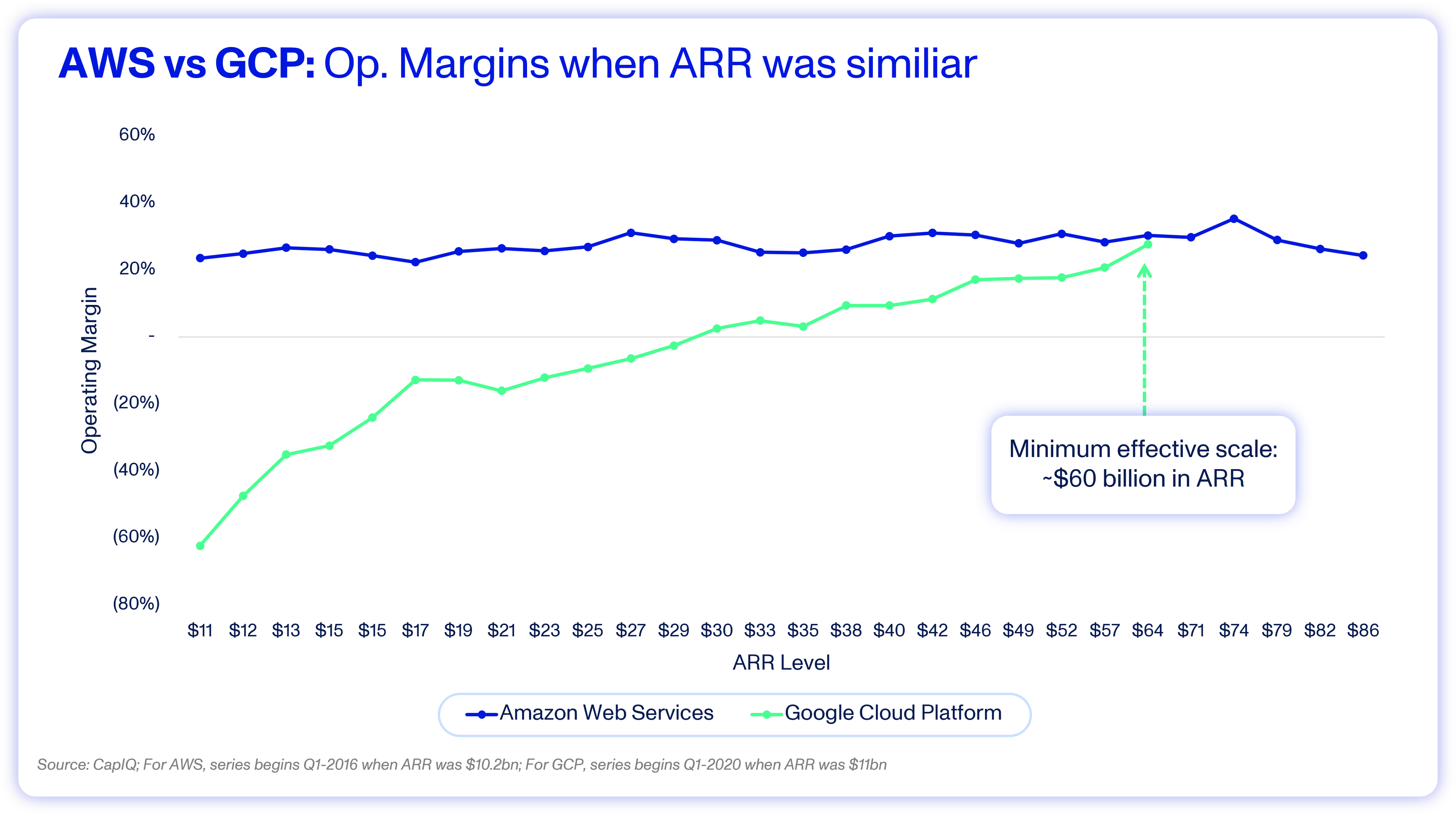

With providers like Amazon dropping prices, they raise the MES higher, further driving concentration. For evidence of this dynamic, consider that Google Cloud only hit breakeven in Q3 2023, doing ~$30bn in ARR. When AWS crossed that threshold (Q4 2018), their operating margins were 28%. In fact, GCP only roughly matched AWS’ operating margins when their ARR crossed $60bn, which likely required >$50bn in capital expenditures. Not quite the realm for startup competition.

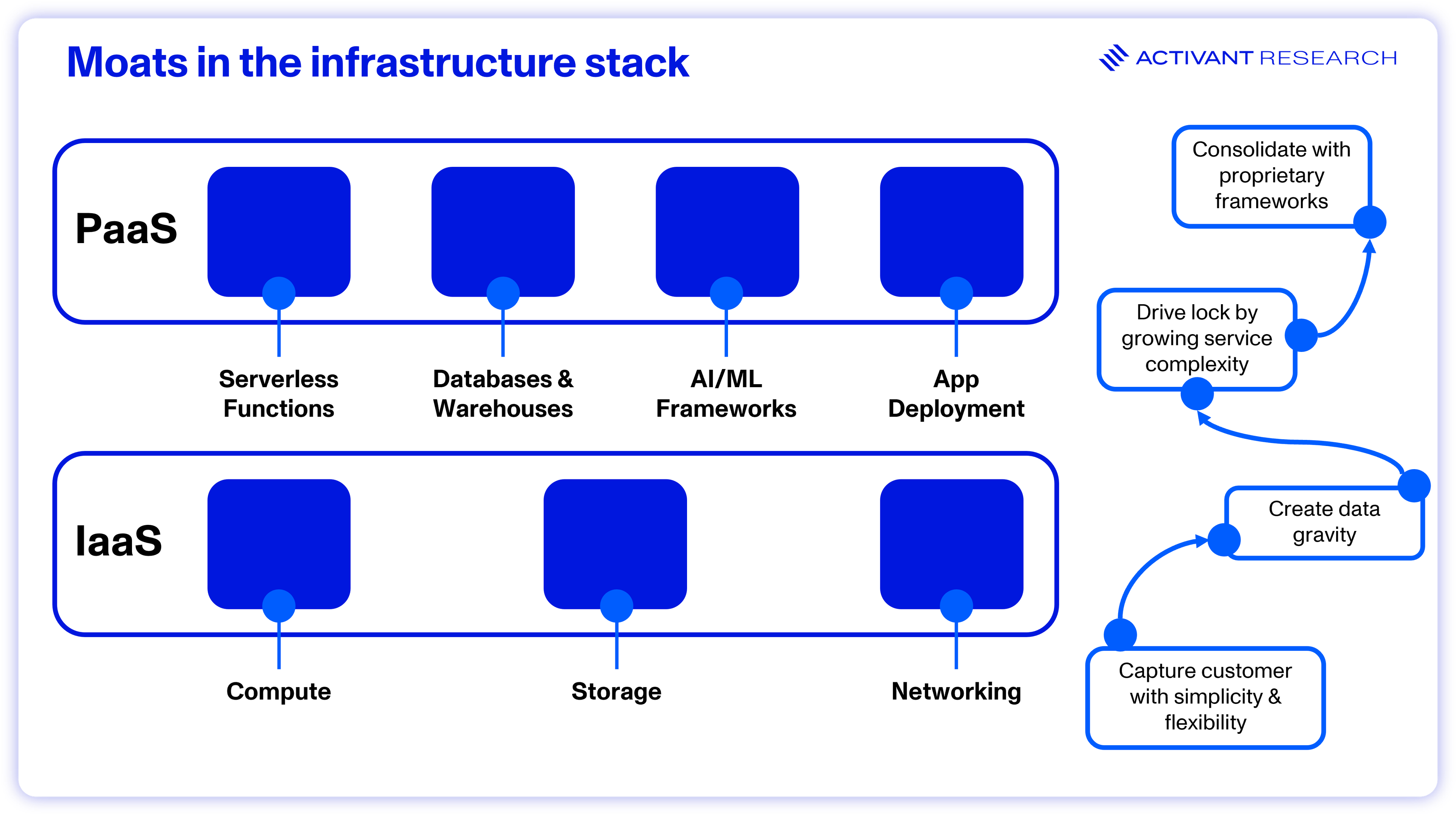

Multi-Layered Vendor Lock-In

Once a customer has chosen a provider, a powerful set of forces works to keep them there. This "vendor lock-in" is a sophisticated, multi-layered system of technical, economic, and contractual barriers.

- Technical Lock-In: The strategic path for Hyperscalers is to acquire customers with standardized, low-margin IaaS and then encourage the adoption of higher-level, proprietary PaaS offerings. Services like managed databases (AWS Aurora, Azure Cosmos DB) or serverless computing (AWS Lambda) offer significant advantages but are built on proprietary APIs. Once an organization builds its core applications on these services, migrating to a different cloud becomes a complex and costly re-architecting project.

- Economic Lock-In: A powerful force known as "data gravity" further entrenches customers. As a body of data grows, it becomes increasingly difficult and costly to move. Hyperscalers amplify this effect through their pricing structures. While it is almost always free to move data into a provider's cloud, it is expensive to move that data out. These data egress fees function as a significant financial penalty for switching providers, another practice that has attracted regulatory scrutiny.

- Contractual Lock-In: Finally, Hyperscalers use contractual mechanisms to secure long-term loyalty. They offer significant discounts, often ranging from 15% to 45%, in exchange for one or three-year commitments to a minimum level of spending through instruments like Savings Plans or Enterprise Agreements. These agreements disincentivize the use of competing clouds by making it more difficult to meet the commitment thresholds required to achieve the best volume discounts.

These moats do not operate in isolation; they form a self-reinforcing system. Capex drives economies of scale, and low cost flexible primitives attract customers. These customers string more services together, creating complex meshes that are harder to switch from. Storage primitives create data gravity, which makes it more cost effective to leverage PaaS from the same vendor, further entrenching switching costs with proprietary frameworks that would require application rewrites to switch off.

The way forward

The Hyperscale providers have built a position in the cloud market which should form the perfect base to capture the growth in AI computing. New entrants simply cannot match their scale, service breadth and distribution advantages. Rather, Neoclouds and Serverless Inference providers need to play by their own rules and as we’ll explore in our next article, that’s exactly what they’re doing.

Neoclouds have turned service breadth into a weakness, offering a simplified and lower cost experience with access to bare metal GPU compute and brand new infrastructure purpose built for AI workloads. While Serverless Inference providers are focusing on developer experience, with elegant APIs that can get your team running AI workloads in a few lines of code, perfectly optimized to cut cold starts and handle highly variable workloads.

The new business models are in place, the open question is what share of the profit pool they can capture.

Endnotes

[2] Bessemer Venture Partners, The BVP Nasdaq Emerging Cloud Index, 2025

[6] Business Tech, Amazon chases after Google cloud price cuts, 2014

[7] JP Morgan CIO Survey, 2025

[8] Google, Q1 2023 quarterly report, 2023; ARR approximated as annualized quarterly revenue

Disclaimer: The information contained herein is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as investment advice. The opinions, views, forecasts, performance, estimates, etc. expressed herein are subject to change without notice. Certain statements contained herein reflect the subjective views and opinions of Activant. Past performance is not indicative of future results. No representation is made that any investment will or is likely to achieve its objectives. All investments involve risk and may result in loss. This newsletter does not constitute an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. Activant does not provide tax or legal advice and you are encouraged to seek the advice of a tax or legal professional regarding your individual circumstances.

This content may not under any circumstances be relied upon when making a decision to invest in any fund or investment, including those managed by Activant. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by Activant. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, Activant has not independently verified such information and makes no representations about the current or enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation.

Activant does not solicit or make its services available to the public. The content provided herein may include information regarding past and/or present portfolio companies or investments managed by Activant, its affiliates and/or personnel. References to specific companies are for illustrative purposes only and do not necessarily reflect Activant investments. It should not be assumed that investments made in the future will have similar characteristics. Please see “full list of investments” at https://activantcapital.com/companies/ for a full list of investments. Any portfolio companies discussed herein should not be assumed to have been profitable. Certain information herein constitutes “forward-looking statements.” All forward-looking statements represent only the intent and belief of Activant as of the date such statements were made. None of Activant or any of its affiliates (i) assumes any responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of any forward-looking statements or (ii) undertakes any obligation to disseminate any updates or revisions to any forward-looking statement contained herein to reflect any change in their expectation with regard thereto or any change in events, conditions or circumstances on which any such statement is based. Due to various risks and uncertainties, actual events or results may differ materially from those reflected or contemplated in such forward-looking statements.